I had to leave the Christian suburbs to thrive as a single woman

Moving away after 12 years relieved a burden I didn't know I was carrying.

Several years ago, when I began thinking about writing books, a colleague said writing a “singleness book” might be a bad idea, because then singleness would be my “brand.” And if I wanted to not be single someday, then becoming an expert on singleness could hinder that. I’m so glad I never wrote a book about singleness, and never will.

(God snort-laughs.)

For related reasons, I hesitate writing about singleness — specifically, how I experienced mine in a suburban Christian milieu in an earlier time in life — because I think of this space as professional, and my marital status is immaterial to my work. I would honestly rather write again about abuse in the church. That abuse is an easier topic to write about than singleness — especially for a woman who is past 30, which let’s be honest used to be the “scary age” and now seems pretty glorious, so full of collagen — that’s how much I don’t want to write this.

But, I’m doing the thing, in part because I imagine some of you find yourselves burdened with a story about singleness, marriage, and what it means to be blessed that is robbing you of joy. And I want to tell you that there are other stories, ones that might be more generative for you, about what it means to live a good life — not an easy life, but a full, rich, and yes, blessed life.

(Also I want to tell you to move to New York City. I am kind of kidding.)

So here is the thing I don’t want to write, about how I used to think it would be very scary, a sign of having been forgotten by God, to be 38 and unmarried, and how the opposite has proven true.

Examining the script

Shortly after undergrad, I moved to Glen Ellyn, in the Chicago suburbs, to start a job at Christianity Today. I ended up living there for 12 years. So much life happened there. Beyond all the professional stuff, it’s where I found my first deep friendships. It’s where I met a few women who are now in the “lifers” category, with whom I have shared deep sorrows and deep joys. These friendships are precious to me.

Glen Ellyn is where I learned how to adult, how to cook dinner and file my taxes and get my oil changed. Speaking of automotive care: It’s where I learned not to accept a car repair quote without first calling Dad (bye bye $1,200). I learned that you will feel better if you eat vegetables, drink water, and go to bed before midnight. All the boring but important stuff.

Glen Ellyn is where I acquired some basic tools from therapy, things like boundaries and gut knowledge and how we’re shaped by our family of origin. It’s where I learned about the Enneagram, for Pete’s sake.

Because Glen Ellyn was the first place I lived as an adult, I couldn’t compare it to anywhere else. I didn’t realize there were things about it that were specific to it — specific to its “social imaginary,” to quote philosopher Charles Taylor. By “social imaginary,” Taylor means how people imagine their life together and then express it — not through theory or ideas, but through “images, stories and legends.” Taylor says a social imaginary accounts for what is both “factual and normative; that is, we have a sense of how things usually go, but this is interwoven with an idea of how they ought to go…” So, a social imaginary is both descriptive and prescriptive. It also connects up with bedrock beliefs about what is right and true.

(It now strikes me that I might be blathering on about Charles Taylor as a way of stalling.)

Because of its proximity to Wheaton College and various ministries and faith-based publishers, that part of the Chicago suburbs is often called a “Christian bubble.” Reader, I could count on one hand the number of people I knew in Glen Ellyn who weren’t Christians. In one apartment building I lived in, everyone wasn’t just a Christian but an Anglican, representing three different parishes in the area. It was a comfortable place, but also a racially and ideologically homogenous place, with an overarching script for what it would or should look like to be a good Christian.

This Christian bubble, I learned, wasn’t a place I could flourish as a single Christian woman.

It gave me a script that defined my life by what I didn’t have.

Glen Ellyn was the place where a well-meaning (I think?) acquaintance told me, then 25, that I shouldn’t get too invested in my work at CT, because it could distract me from getting married and having kids. She was then in her 40s, and single. She didn’t explain why work would prevent getting married and having kids — lots of people do both at once — but the comment implied that I needed to make a choice, and that work, in this false dichotomy, was the wrong one.

Glen Ellyn was the place where, at a wedding shower, someone prayed over the bride-to-be that God had made her and her fiancee to be husband and wife “before the foundations of the world.” If your theology emphasizes God’s sovereignty, then yeah, this checks out. But it also raised questions for me about God’s sovereignty in the lives of people who never found a spouse but desperately wanted to, or whose spouse abandoned the marriage and/or left the faith. It certainly raised the stakes for dating — i.e., is this guy sitting across from me at Starbucks the person God created as my spouse? How do I know? Did God create the eHarmony algorithm before the foundations of the world?

Glen Ellyn was the site of many beautiful weddings and baby showers and other important celebrations of good things. I was at an age where lots of people get married and have children, so the frequency was to be expected. And also, in that particular social imaginary, these gatherings seemed to mark official entry into adulthood, into “real life” finally starting. (Who gets to say whose life is real?) Maybe I was projecting, but they also carried a whiff of relief, specifically for women, at having found an escape hatch out of the unblessed life.

Glen Ellyn — and it should be said, most suburbs — was a place where people live in single-family homes, where its very physical structure communicates that the nuclear family is normal and normative. Living in an apartment there always felt like a holdover place, like a thing you endure and make the most of until you have a mortgage and regular play dates at the park.

Glen Ellyn was the place I saw a woman in her 50s — a highly accomplished leader at a Christian institution, a beloved member of her community — weep openly at a women’s retreat, asking aloud why God hadn’t sent her a husband. Her pain was palpable, and I felt for her.

And also, reader, it scared me. That moment — of this woman weeping, because God had seemingly withheld a good thing, perhaps God’s best thing, for mysterious reasons — crystallized into catastrophizing about the future. My future. What if God never answers this prayer? What if I am left out of this blessing while so many friends and peers get it? What will that mean about God? Is God trustworthy? Is he good?

In darker moments, I would think about her crying, and worry that would be me someday.

I didn’t have access to a story about a single woman who reaches her 50s and is blessed. Not just happy or #fiftyflirtyandthriving, but distinctly seen and known and directly blessed by God in the fullness of herself and her life.

I didn’t know at the time that there might be other stories.

Choose Your Pain

To be clear: In this time, I wanted to be married. And today, I’d articulate it a bit differently, but the desire for a companionate, lifelong, monogamous partnership — what many people call “marriage” lol — is still there.

But I’m also wanting to say that our desires don’t exist in a vacuum. They are propelled or hindered by the communities that shape and ground us. So my desire for marriage was, in that context, turbo-charged with a collective identity and spiritual superlative. I didn’t want to be left out.

As a result, I put up with shenanigans from single men in my 20s that I would never today. I experienced incredible anxiety over losing a few quasi-relationships, even while I wasn’t even sure I liked the guy, far less that he was a suitable life partner. There were no countervailing narratives available to quell my terrible anxiety.

I got engaged at age 27, and recognized even then how quickly the “Christian woman preparing for marriage” identity took over, no doubt confirmed by gushing reactions on social media. I mean, I got the thing, right? And now I get to fill out a gift registry and get the Vitamix. It’s all happening.

The engagement ended, and that was crushing. People say some sideways things after a broken engagement and other losses. Sometimes they don’t know what to say, and I get that. I was also supported in that time by friends who knew the particulars. It could have been worse. And I can say with my whole heart today that it was very good we didn’t get married.

And also, in the aftermath, I wish someone had tapped my younger self on the shoulder and gently offered her a different script. Had suggested, for example, that a bad marriage is worse than no marriage, even if the guy is a Christian and ticks all the boxes. That a life can appear blessed from the outside, in all the quick ways we assess other people, and can be a mess on the inside. That even good, solid marriages come with challenges and anxieties and griefs that don’t make it to Instagram but are real in the way an actual human life is real. That every life path comes with unique joys and unique pains, that there’s no actual script that can omit the hard bits.

I wish I had been given an understanding of blessing beyond external markers. I genuinely believed, and had reinforced, that having a husband and family would be the thing I could point to to know that everything was going to be okay.

Anything you look to for ultimate security besides God is an idol. Of course I knew that. Pastors in Christian bubbles say this ad nauseam, and warn young people not to idolize marriage and family. But I struggle to hear them, because a qualification for pastors in Christian bubbles is that they be married with children. And many churches are structured around the family experience. You can talk a lot about an idol, but if you model and speak of marriage as you having won the spiritual lottery, no wonder I struggle to spot the idol as it’s operating in my heart and imagination. And that’s on me, but I want to say it’s on us, too.

Not Afraid of the Future

I thought that if I didn’t have the thing, then I wouldn’t be happy.

Here’s the thing: If you can’t be happy without the thing — the job, the house, the wardrobe, the vacation, the baby, the sex life, the friendship, the social media following, the 401k, the dynamic church — then you won’t be happy even if you get it.

If you can’t see your life for the blessing that it is — in its actual, on-the-ground, moment-to-moment unfolding, with all its unmet longings and griefs and discomfort and boredom — then you won’t see the blessing even when your longing is met or your grief subsides or perhaps you find incredible joy with another person in this life.

I couldn’t see my life for the blessing that it is, because it was defined by something I lacked. And that is a paltry life script, and a short one, too.

Maybe I could have found another, better script any number of places, including Glen Ellyn or another suburb. Maybe I needed to just grow up, to let age produce wisdom like a fine wine, to use a cliche that finds much purchase among on Etsy shoppers.

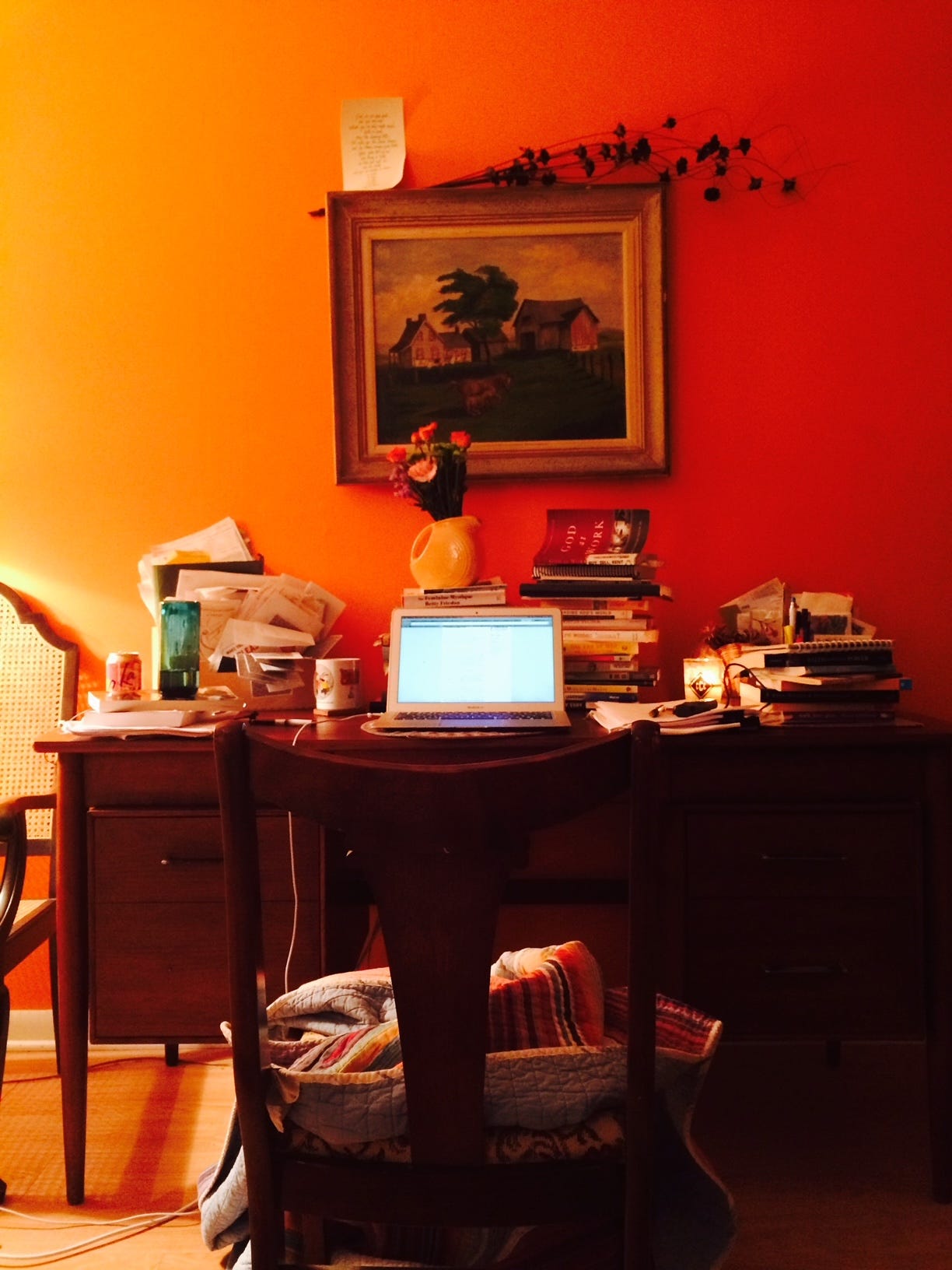

But as things actually unfolded, I found a better script by leaving the Christian bubble entirely. I didn’t realize until moving to NYC in 2018 that I had been suffering on the edges of the bubble for years, trying to convince myself and others that some future life without a husband and children wouldn’t preclude richness and joy. Moving to NYC was one of the best decisions I could have made, in that it relieved a burden I didn't know I was carrying. I didn’t even realize it was a burden until I moved away, which reinforces how powerful a social imaginary is until you move into a new one.

I’ll write about NYC soon, and why it has been great — again, not easy, but full, rich, exciting, and not alienating. But for now I’ll say its greatest gift has been relieving me of fear of the future. I wish I had known sooner that I needn’t be afraid. —KB

Thanks for this. I got married + had kids in my 20s, and your life represents an alternative I've often wondered about and at times longed for - though like you, I'm grateful for my choices and where I am today. More dialogue from both sides of this "divide" would be helpful. As would more opportunities to interact in one anothers' lives as women, generally.

A brave, mature, wise and very helpful piece that you've written.

(and I never thought I would gasp with delight at a photo of Billionaire's Row!)